President Trump greets Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni outside the West Wing of the White House on April 17. Meloni has been called a “Trump whisperer” who could bridge the gap between the U.S. president and European leaders.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Win McNamee/Getty Images

Donald Trump’s initial ascent to the presidency inspired right-wing populist politicians around the world, many of whom sought to emulate his anti-establishment and anti-immigrant messaging. But in his second term, Trump’s aggressive trade policies and confrontational stance toward America’s allies are threatening to turn that populist wave into a dangerous undertow.

Now the “Trump bump” that populist candidates had anticipated is turning into a “Trump slump.” In some countries, including those facing national elections soon, political leaders who’ve advocated a homegrown style of MAGA are suddenly scrambling to distance themselves from the U.S. president.

“Many worried that Trump’s electoral victory would create a tidal wave in support of extreme right populist parties across the world while encouraging them to intensify their extremism,” says Vivien Schmidt, a professor emerita at Boston University and a visiting fellow at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy.

But Trump’s tariffs — which have a baseline of 10% along with steeper rates targeting certain countries and industries — have been a particular flashpoint. The tariffs “have put populist leaders on the back foot, and may ironically very well push them to greater moderation,” Schmidt says.

Canada’s Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre speaks during a campaign event on April 14 in Montreal. A Trump backlash is a major cause of the Conservatives’ stalled momentum and a resurgence for the Liberals, observers say.

Andrej Ivanov/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrej Ivanov/Getty Images

Take Pierre Poilievre, the leader of Canada’s Conservative Party, who has embraced anti-establishment and anti-“woke” rhetoric and has even been labeled “Canada’s Trump” by some observers. In the lead-up to the country’s elections next Monday, Poilievre’s Conservatives initially surged, holding a commanding 45% to 22% lead in January over the governing Liberals of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who stepped down last month. The exit of Trudeau, who had long been on thin ice with voters, was clearly a factor, but a Trump backlash is a major cause of the Conservatives’ stalled momentum and a resurgence for the Liberals, observers say.

The dominant issue in Canada is Trump’s “looming influence in reshaping our politics,” says Semra Sevi, an assistant professor in the political science department at the University of Toronto. “The electorate is looking for serious leaders with credible plans” who can confront, not accommodate, the U.S. president, she says.

Poilievre has largely abandoned his “Canada First” slogan, with its parallels to Trump’s “America First.” As the U.S. president ramped up provocative talk about annexing Canada in the early weeks of his term, Poilievre pushed back, declaring, “Canada will never be the 51st state.”

Jennifer McCoy, a professor of political science at Georgia State University in Atlanta, has studied populist movements across the globe. “Calling Canada’s prime minister ‘governor’ and suggesting it become the 51st state … has backfired,” for Trump, she says. “Canadians are insulted and moving away from conservative populism as a result.”

If the election had been held last year, Poilievre’s Trump-style of politics would have helped, she says. But the Conservatives are now finding it difficult to shake off their association with Trump. The Canadian populist “needed to pivot and he needed to do that hard and early on and he misread the moment,” Sevi says.

Until recently, Australia’s conservative opposition had “the wind at its back”

Opposition leader Peter Dutton speaks on April 11 in Perth, Australia. The Australian federal election is scheduled to be held on May 3. Dutton’s conservative Coalition is on the back foot after leading earlier this year.

Matt Jelonek/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Matt Jelonek/Getty Images

The story is similar in Australia, where voters head to the polls on May 3. Opposition leader Peter Dutton, a right-wing populist who once described Trump as “a big thinker,” and has called for cutting off funding for schools which he deems to have a “woke” agenda, is challenging Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Dutton’s Liberal Party and its National Party partner, known as the Coalition, were ahead in the polls earlier this year but have since lost ground.

“The Coalition initially had the wind at its back … now they’re in survival mode,” says Ryan Neelam, director of the public opinion and foreign policy program at the Sydney-based Lowy Institute.

That slide closely tracks the first months of the second Trump presidency, which has also been accompanied by a sharp drop in Australian trust toward the U.S. According to a new Lowy poll, the number of Australians who believe the U.S. can be trusted to act responsibly on the world stage has plunged over the past year, from 56% to 36%.

Neelam says that is a record low since the institute began asking the question in 2006. It’s part of what he describes as “a categorical rejection of Donald Trump’s policies” among Australians.

“Tariffs hit a nerve … splashed across the media, [it] became a political issue,” he says, adding that 81% of Australians surveyed disapprove of the tariffs. Three-quarters of Australians also disapprove of Trump negotiating with Russian President Vladimir Putin over Ukraine.

Dutton has attempted to distance himself from aspects of Trump’s agenda, especially on trade. He criticized the U.S. tariffs, saying Trump’s self-declared “Liberation Day,” when reciprocal tariffs went into effect, was “a bad day for our country.”

But in one remark at a campaign rally earlier this month, Sen. Jacinta Nampijinpa Price — the shadow minister for government efficiency, who has pledged to implement an Elon Musk-style overhaul of federal spending — introduced Dutton by declaring that the Coalition would “make Australia great again.” The remark prompted National Party leader David Littleproud to enter damage-control mode, dismissing the comment as a “slip of the tongue.” Adding fuel to the controversy, Price and her husband also shared a photo on social media of the couple wearing “Make America Great Again” hats.

Canada and Australia aren’t the only places where association with Trump’s brand of politics is dragging down right-wing populists, straining ties that in recent years have seen them “increasingly [build] up a network to learn from each other — borrow lessons, rhetoric and policies,” according to McCoy.

Parliamentary systems present obstacles for populists

As Trump’s appeal fades in many countries, his ties with like-minded foreign leaders appear increasingly fragile. Part of the reason, says Boston University’s Schmidt, is structural: “Most of these leaders operate within parliamentary systems,” she explains. “That means navigating coalition partners — you don’t have the same unilateral power a U.S. president does.”

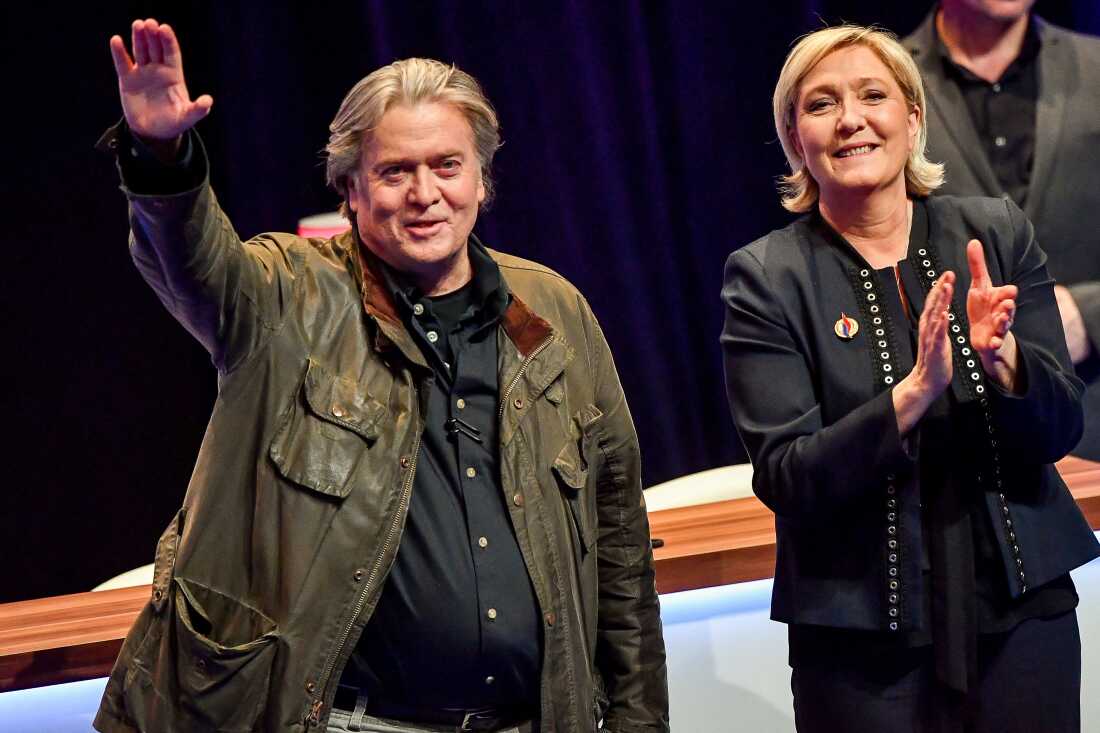

In 2018, Trump’s then-senior strategist Steve Bannon visited various populist movement leaders in Europe, including Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s far-right National Front party at the time, where the two suggested it was the beginning of closer ties. Le Pen, who later rebranded the party as the National Rally, once embraced Trump as a political role model. But now she seems to view him more as a liability amid polling suggesting Trump is a drag on her political fortunes.

France’s far-right party president Marine Le Pen (right), applauds former presidential adviser Steve Bannon after his speech during the party’s annual congress, on March 10, 2018, at the Grand Palais in Lille, France.

Philippe Huguen/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Philippe Huguen/AFP via Getty Images

That said, Le Pen, who was forced to step down as her party’s leader, may have bigger problems than her association with Trump: She was convicted last month of embezzling European Union funds and barred from holding public office — an obstacle that could derail her 2027 presidential ambitions.

In Germany, the performance of the avowedly anti-immigrant AfD party at the polls in February has been a notable exception, when it surged to become the second-biggest party in Germany’s Bundestag. Ahead of the elections, Vice President Vance met with the party’s leader and endorsed it as a political ally. Yet public sentiment toward Trump remains overwhelmingly negative, according to a poll from early March, with only one-in-seven Germans viewing him favorably.

Meanwhile, other right-wing leaders, such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban, whom Trump has repeatedly praised in the past, seem to remain firmly ensconced, likely more because of his increasingly authoritarian control over democratic institutions than genuine appeal to voters.

Italy’s “Trump whisperer” might be able to split the political difference

President Trump meets with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni in the Oval Office at the White House on April 17.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Win McNamee/Getty Images

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who visited the White House in recent days to meet with Trump, may represent a way forward for right-wing populists wanting to balance their political survival while steering a middle road, observers say. She’s been seen as a “Trump whisperer” who could bridge the gap between the U.S. president and other European leaders, some of whom Trump has openly derided. Trump has praised the right-wing Meloni, calling her “a fantastic person and leader.”

But she has made a point of demarcating her positions carefully. The two leaders appear to see eye-to-eye on immigration and cultural conservatism, but on the war in Ukraine, unlike Trump, Meloni has been careful to unequivocally label Putin the aggressor. She said U.S. tariffs are “wrong” but offered to help make a deal between the White House and the EU to lift them.

“Meloni is a very clever politician,” says Schmidt. “What she’s doing on the economy and Ukraine is very mainstream, center-right.”

Georgia State University’s McCoy agrees that Meloni’s stance splits the difference between Trump and a more mainstream European view. “Meloni is a very anti-immigrant conservative on cultural issues — but also pro-EU and pro-Ukraine,” she says. “It’s a very interesting mix.”